“Disease is the Love of Two Alien Kinds of Creatures”: Desire as Pathogen in David Cronenberg’s Shivers

Shivers is one of David Cronenberg’s oddest films: it is his first commercial, feature-length film; it is little-known; it is rich with allusions (William Blake, Sigmund Freud, Thomas Hobbes, St Luke the physician); and, like most of his films, Shivers makes extensive use of binaries. What I’d like to do is examine just one set of binaries on which much of the film’s horror is based, but one that is less obvious than a first viewing would suggest. My thesis is obvious, however: desire—instead of the parasites or infected sex maniacs—is used to horrify the audience.

Since what we’re about to watch is something you’ve likely never seen or even heard of, I want to quickly outline the film. WARNING: Here be spoilers.

The first scene is a montage of binaries, visualizing the confusion that results from their coexistence. In Starliner Towers, an ultra-mod high-rise condominium, we see a slick property manager “hunt” prospective renters; interspersed with this is the actual “hunt” and mutilation of a young woman by a much older man. The scene ends with the man slitting his own throat with a scalpel. From here the film proceeds along two complementary lines—a detective story in which the main characters try to figure out just what is going on, and a horror story in which the main characters try to resist infection. As the detective yarn unfolds, we learn the older man was a scientist who created a parasite that is half aphrodisiac, half venereal disease—with which he hoped to turn the world into a giant orgy. As the horror plot unfolds and the infection spreads exponentially, Dr. Roger St Luc, the condo’s medical officer, and Nurse Forsythe (Lynn Lowry in her post-The Crazies and pre-Cat People role) try in vain to resist. Eventually, she’s infected and finally infects St Luc.

I notice that when I give the bare outline of the plot, the film sounds like an on-the-cheap forerunner of Resident Evil or a reimagining of Romero’s Night of the Living Dead. For most first-time viewers, the aspects that make Shivers a horror movie are the parasites and the infected. When we get a good look at them, the parasites look like phallic turds—pretty disgusting if the special effects weren’t so laughable. But they invade the boundaries of the body and colonize people—pretty scary. The infected, unlike Romero’s zombies, look mostly normal, but they are aggressive, and the film depicts them all as sexually transgressive.

But I wonder…there is a fear of pathogen in the film, but the fear isn’t elicited by the squishy, brown parasites or the infected, bare-chested janitor who advances on our hero in the basement boiler room. Instead, uncontrolled desire is the pathogen that elicits horror in the audience because the film suggests that there’s nothing inhuman about the actions it depicts. We are all already infected.

But what about those parasites? How are they not horrific? What about the infected? The former is disgusting and the other threatening, but that hardly counts for horrific. In fact, the parasites cause permanent damage to only one character and aren’t directly responsible for a single death. The infected are sexual predators, but they’re only responsible for one death in the film; the supposedly healthy characters kill five people. So I’d like to suggest that the parasites and infected are scary but not horrifying.

That likely needs some explanation because you’re probably wondering how “scary” and “horrifying” are different. What I mean by “scary” is the scene or action that may frighten us, but that we can leave behind. To use an example from the era of Shivers: in Tobe Hooper’s Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), it’s damn scary when Leatherface comes out of nowhere and smacks Kirk with the hammer, dragging him into the house and slamming the steel door. But the dinner scene is horrifying because Sally is trapped and we finally understand that the family is operating by a set of rules known only to them. Norman Bates in that wig also fits the bill. Regan MacNeil vomiting pea soup does not. The horrific, for my purposes, is that set of disturbing aspects of a film or text that you can’t quite shake, so it seems to me that unbound desire is the really horrific aspect of Shivers. It’s the sexual violence and transgression that really make the film disturbing.

Norman Bates in that wig also fits the bill. Regan MacNeil vomiting pea soup does not. The horrific, for my purposes, is that set of disturbing aspects of a film or text that you can’t quite shake, so it seems to me that unbound desire is the really horrific aspect of Shivers. It’s the sexual violence and transgression that really make the film disturbing.

Norman Bates in that wig also fits the bill. Regan MacNeil vomiting pea soup does not. The horrific, for my purposes, is that set of disturbing aspects of a film or text that you can’t quite shake, so it seems to me that unbound desire is the really horrific aspect of Shivers. It’s the sexual violence and transgression that really make the film disturbing.

Norman Bates in that wig also fits the bill. Regan MacNeil vomiting pea soup does not. The horrific, for my purposes, is that set of disturbing aspects of a film or text that you can’t quite shake, so it seems to me that unbound desire is the really horrific aspect of Shivers. It’s the sexual violence and transgression that really make the film disturbing. (I should stop for a moment here and note there are quite a few sexualities depicted here that we don’t necessarily consider transgressive. But this is 1975—six years after Stonewall and only four years after the National Women’s Political Caucus was formed: the list of mainstream sexualities was still pretty narrow, so when I label something “sexually transgressive” know that I am talking within the context of the film only.)

In the context of the film, we see almost no sexual desire in a positive light. We’ll see only violent heterosexuality. We’ll also see unwilling participation in group sex, overt lesbianism (on which Cronenberg see ms to linger), subtle male homoeroticism (which provokes some of the most vigorous responses from St Luc), pedophilia, S&M, and incest. And I don’t even know how to categorize Barbara Steele’s character being raped by a parasite in the bathtub (parasite sodomy?).

subtle male homoeroticism (which provokes some of the most vigorous responses from St Luc), pedophilia, S&M, and incest. And I don’t even know how to categorize Barbara Steele’s character being raped by a parasite in the bathtub (parasite sodomy?).

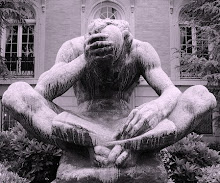

What’s horrific is that humans are capable of—and often prone to—everything we see in the film. If anything, the parasites unchain desire in the characters. And this is exactly what Hobbes wanted to do. Linsky tells us: “Hobbes believed ‘Man is an animal who thinks too much, an over-rational animal that’s lost touch with its body and its instincts,” and we learn that the parasite was designed to “turn the world into one beautiful, mindless orgy.” It works all too well, and seeing his experiment work, Dr. Hobbes (just like Victor Frankenstein), recoils in horror, killing his young lover (the twelve-year-old-girl all grown up) and himself to try to stop the spread of the pathogen. So the film presents the old binary of cool reason and flaming desire, and shows us what happens when the balance skews too far toward the animalistic side: it’s probably no accident that Erica Jong’s Fear of Flying—and its popularization of the “zipless fuck”—was published two years before Shivers was released. The film is almost certainly responding to this notion and the ongoing sexual revolution—meditating on a limit case.

subtle male homoeroticism (which provokes some of the most vigorous responses from St Luc), pedophilia, S&M, and incest. And I don’t even know how to categorize Barbara Steele’s character being raped by a parasite in the bathtub (parasite sodomy?).

subtle male homoeroticism (which provokes some of the most vigorous responses from St Luc), pedophilia, S&M, and incest. And I don’t even know how to categorize Barbara Steele’s character being raped by a parasite in the bathtub (parasite sodomy?). What’s horrific is that humans are capable of—and often prone to—everything we see in the film. If anything, the parasites unchain desire in the characters. And this is exactly what Hobbes wanted to do. Linsky tells us: “Hobbes believed ‘Man is an animal who thinks

Cronenberg himself seems to confirm this. As steeped as he is in Freud (see The Brood and Dead Ringers, especially), it should be no surprise that he thinks “civilization is repression. You don’t get civilization without repression of the unconscious, the id.” Starliner Towers and St Luc, then, are civilization with all the repressive social controls. The parasite removes those controls and leaves the infected free to pursue individual desires without regard for the welfare of the civilization as a whole—as “nasty” and “brutish” as anything Dr. Hobbes’ namesake ever imagined.

Nurse Forsythe perhaps says it best in her monologue toward the end of the film. She tells St Luc about a dream she’d had the night before:

“in this dream I find myself making love to a strange man. Only I'm having trouble, you see, because he’s old and dying, and he smells bad and I find him repulsive. But then he tells me that everything is erotic, that everything is sexual…He tells me that even old flesh is erotic flesh, that disease is the love of two alien kinds of creatures for each other…That talking is sexual, that breathing is sexual, that even to physically exist is sexual…And I believe him, and we make love beautifully.”

(Fun fact: in the original script, Cronenberg has Forsythe making love to Freud himself.)

Now, she’s infected when she shares this with St Luc, but I want to point out that she had the dream the night before when she was still healthy—and this again points to the latent desire in every human, desire that is enabled by the parasite but not caused by it. St Luc, one of the most asexual characters in a Cronenberg film, responds as civilization. He represses the expression of transgressive desire by promptly punching Forsythe in the mouth and gagging her. But he does not kill her (for civilization cannot kill desire); instead he totes her around for a bit longer. The two are eventually separated, and St Luc holds out until he’s trapped in the condo’s swimming pool by a horde of infected.

Now, she’s infected when she shares this with St Luc, but I want to point out that she had the dream the night before when she was still healthy—and this again points to the latent desire in every human, desire that is enabled by the parasite but not caused by it. St Luc, one of the most asexual characters in a Cronenberg film, responds as civilization. He represses the expression of transgressive desire by promptly punching Forsythe in the mouth and gagging her. But he does not kill her (for civilization cannot kill desire); instead he totes her around for a bit longer. The two are eventually separated, and St Luc holds out until he’s trapped in the condo’s swimming pool by a horde of infected.

A swimming pool.

Cronenberg could not have picked a more evocative metaphor because in Freudian dream psychology, water is one of the main metaphors for the unconscious. What we end up with, then, is St Luc—who coolly discussed the finer points of parasites and smoked a cigarette as Forsythe seductively writhed out of her nurse’s uniform, who flees from three over-sexed women in a pool as if they were Romero’s zombies—St Luc, the patron saint of medicine and physicians, is literally and figuratively submerged in the pool of his unconscious. Hands in the air, he is baptized into desire. All his inhibitions are washed away.

With his fall, we are ushered into the world of unchecked desire: old men desiring young women, old women desiring young men, men desiring little girls, fathers desiring daughters, men desiring men, women desiring women, and—for some reason—twin girls wearing leashes and dog collars. The parasite returns humanity to a more animalistic state. The real horror of Shivers, then, stems from human nature: the performance of desires we’ve all had but repressed is that part of Shivers that is horrific—because it nudges, if only for a moment, our own horrific unconscious into stark outline. As Tom Stoppard’s Guildenstern so eloquently puts it, “it’s like being ambushed by a grotesque,” but a grotesque that we carry within us always.

The parasite returns humanity to a more animalistic state. The real horror of Shivers, then, stems from human nature: the performance of desires we’ve all had but repressed is that part of Shivers that is horrific—because it nudges, if only for a moment, our own horrific unconscious into stark outline. As Tom Stoppard’s Guildenstern so eloquently puts it, “it’s like being ambushed by a grotesque,” but a grotesque that we carry within us always.

The parasite returns humanity to a more animalistic state. The real horror of Shivers, then, stems from human nature: the performance of desires we’ve all had but repressed is that part of Shivers that is horrific—because it nudges, if only for a moment, our own horrific unconscious into stark outline. As Tom Stoppard’s Guildenstern so eloquently puts it, “it’s like being ambushed by a grotesque,” but a grotesque that we carry within us always.

The parasite returns humanity to a more animalistic state. The real horror of Shivers, then, stems from human nature: the performance of desires we’ve all had but repressed is that part of Shivers that is horrific—because it nudges, if only for a moment, our own horrific unconscious into stark outline. As Tom Stoppard’s Guildenstern so eloquently puts it, “it’s like being ambushed by a grotesque,” but a grotesque that we carry within us always.