But for the love of Mr Peanut, let's not blame ourselves. People have been worried about tainted peanut butter, tomatoes, spinach, etc. for years now, and the latest news from West Texas isn't helping any. From The Raw Story:

But for the love of Mr Peanut, let's not blame ourselves. People have been worried about tainted peanut butter, tomatoes, spinach, etc. for years now, and the latest news from West Texas isn't helping any. From The Raw Story:The shrieks over the latest food-bourne illness outbreak has made me start thinking. What was it that we said before? From the NYT on 12 December 2006:The discovery of dead rodents and bird feathers in a Plainview, Texas plant of the Peanut Corporation of America, already implicated in a deadly salmonella outbreak, prompted a recall of all its products, officials said....

The company's facility in Blakely, Georgia has been blamed for a widespread food poisoning outbreak knowingly shipped contaminated peanut butter and had mold growing on its ceilings and walls.

The salmonella outbreak took place between September 1 and January 9, with 501 people infected in 43 states and one more person reported ill in Canada, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), which is collaborating with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on the investigation....

An FDA inspection report released Wednesday found 12 instances between June 2007 and September 2008 where the firm's own testing revealed that its products were contaminated by salmonella and the PCA nonetheless shipped the product.

"Two outbreaks of bacterial poisoning from fresh produce over the past three months, and a possible third that is still under investigation, raise doubts about the Food and Drug Administration’s ability to inspect and monitor conditions on the nation’s farms and in the plants that package and process their produce....So, the NYT wants us to load more regulatory duties onto the backs of agencies that have proven they can't keep us safe. I wonder why they can't? Those with a Liberal bent will tell you it's because they are underfunded. Those with a Conservative bent will tell you it's because they're government agencies and breed laziness. Either way, it's not the agencies' fault. It's ours.

Meanwhile, the agency’s workload has been rising steadily as health-conscious Americans eat more fruit and vegetables....At a minimum, Congress needs to provide the F.D.A. with more money and more inspectors to monitor the safety of fresh produce all the way from field to consumer. It should also abandon the fiction that voluntary guidelines to ensure safe food production can do the job, and insist instead on some kind of mandatory regulation. It is also time to revive the long-languishing notion that all of the government’s disparate food regulation activities should be combined into a single, fully empowered agency."

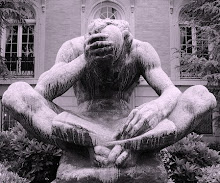

We've bought into the agri-business model hook, line, and sinker. We got hooked, reeled in, and now we're sunk. When/if we think of farmers, we usually think of Old McDonald's farm.

But it's more like Old McDonald Farms LLC, a subsidiary of ConAgra Foods.

But it's more like Old McDonald Farms LLC, a subsidiary of ConAgra Foods. When you rely on something as big as the Peanut Corporation of America, you are asking for trouble because you're relying on a large corporation to act ethically. A corporation may be legally considered a person, but it cannot be morally or ethically considered a person. Sooner or later, the corporation acts dishonestly in service of the bottom line or its shareholders. Wendell Berry, in his Unsettling of America, gives the striking example of the Sierra Club investing in Exxon in the 70s (17). To expect otherwise is to expect the snake not to bite the turtle.

When you rely on something as big as the Peanut Corporation of America, you are asking for trouble because you're relying on a large corporation to act ethically. A corporation may be legally considered a person, but it cannot be morally or ethically considered a person. Sooner or later, the corporation acts dishonestly in service of the bottom line or its shareholders. Wendell Berry, in his Unsettling of America, gives the striking example of the Sierra Club investing in Exxon in the 70s (17). To expect otherwise is to expect the snake not to bite the turtle.So, like Berry, I say that we should be more "responsible consumers," which would necessitate us becoming critical consumers (we would "refuse to purchase the less good"), moderate consumers (we would know our "needs and would not purchase what [we] did not need"), and--at least partial--producers (24). Berry contends:

The household that prepares its own meals in its own kitchen with some intelligent regard for nutritional value, and thus depends on the grocer only for selected raw materials, exercises an influence on the food industry that reaches from the store all the way back to the seedsman. The household that produces some or all of its own food will have a proportionately greater influence....[The producer/consumer] can choose, and exert the influence of his choosing, because he has given himself choices. He is not confined to the negativity of his complaint. (24-25)Now what the NYT--and everyone who's carping about tainted food and evil corporations--are advocating is the confinement of the consumer by "the negativity of his complaint"; in some ways the expectations we've placed on the FDA, the USDA, and corporations who provide our food have injected a sense of learned helplessness in the average American. We don't take responsibility for our food choices because we have ceded our responsibility--and, therefore, our power--to organizations. These organizations are theoretically beholden to us, but they are so big, they have no inherent self: they remove the individuals who comprise them from the stated purpose of the organization and from personal responsibility. Thus, the CEO who ships jobs overseas because it is better for the shareholders, though it is worse for the country in which he lives. Thus, the geologist who explores for the oil that eventually pollutes the air his child will breathe. Thus the FDA agent who is pressured to do more inspections and does them more quickly or sloppily which eventually leads to peanut factories that have rat feces and feathers above the processing area.

This would not, of course, happen if we returned to a regional or local model of food production.

Michael Pollan has written about the results of agri-business, and Carlo Petrini has made it his mission in life to evangalize the slow food movement. We don't have to choose one of the other, however. Certainly, we could create NeoVictory Gardens, a modern version of something our grandparents did during World War II. This is a radical change, but it's also a change that some people are lamenting Bush didn't urge us to make--that is, war sacrifices. (Again, I ask where's the personal responsibility? Why does someone have to force us to effect change in our lives?)

Michael Pollan has written about the results of agri-business, and Carlo Petrini has made it his mission in life to evangalize the slow food movement. We don't have to choose one of the other, however. Certainly, we could create NeoVictory Gardens, a modern version of something our grandparents did during World War II. This is a radical change, but it's also a change that some people are lamenting Bush didn't urge us to make--that is, war sacrifices. (Again, I ask where's the personal responsibility? Why does someone have to force us to effect change in our lives?)Of course, a NeoVictory Garden is a difficult change to make beause some people don't have yards, and a window box can only produce herbs in most cases. So why not shop at farmer's markets? Why not purchase locally-made or locally-sourced foods? It's more expensive, but you're paying for inefficiency. And that is a good thing, I think.

Ineffeciency in the food industry means more jobs because of redundancy--more small farms and processing plants scattered throughout the nation means more managers, more farmers, more machinery, more people to produce that machinery, etc.

It also requires more responsibility for the consumer. More smaller companies also means less effective centralized oversight, so the FDA can't save the day (and also can't be the punching bag when people get sick). Let's imagine a company called The Willamette Valley Peanut Corp. that services only the Willamette Valley area. It would be more responsibile to and less removed from it consumers. Compare the Peanut Corporation of America, which supplied millions of peanuts to dozens of different companies making everything from Publix's crap-tastic Spicy Trail Mix to Clif Bars, which are supposed to be "all natural" and "70% organic." But people had never heard of the PCA before, and it took a lot of work to figure out how far its tainted products had spread throughout America. Willamette Valley Peanut Corp., on the other hand, would supply to just regional companies, would be more visible to its end consumers, and would suffer from competition if it produced an inferior peanut. These things aren't (or weren't) real concerns for PCA--especially the last one since the company was too big for smaller, localized companies to compete with. Even if the fictional WVP grew to dominate the area, it's not as hard to start up and compete with a regional power as it is to compete with the Wal*Mart of peanut production.

The end result of all of this worry and hand-wringing is likely to be more regulation, larger government, and higher taxes. I am not so die-hard libertarian that I cannot see the value in these things. Sometimes. But this is not one of those times. If we were able to reward inefficiency and regionalization in our food production, we would be able to more easily re-assume and exercise our duties as consumer-producers, responsible consumers, and individuals. I should acknowledge that this little tirade, as Berry admitted in his book, is implicitly (and now explicitly) directed against liberalism as it is practised today.

It has become, to some extent at least, an argument against institutional solutions. Such solutions necessarily fail to solve the problems to which they are addressed because, by definition, they cannot consider the real causes. The only real, practical, hope-givingway to remedy the fragmentation that is the diseaseof the modern spirit is a small and humble way--a way that a government or agency or organization or institution will never think of, though a person may think of it: one must begin in one's own life the private solutions that can only in turn become public solutions. (23)

I'm not Bob Barr and I think that sometimes larger government and powerful centralized governmental organizations are the answer. I would love to hear how Libertarians think the airline industry would work without the FAA or how well Southern Blacks would be educated without the Dept. of Education. But organizations remove the individual and her sense of importance from the equation, and when that happens moral choices don't carry the weight they once did (since no one will notice or be directly harmed by our actions). Top-down, organizational approaches are sometimes useful. Sometimes, however, they are a fiction useful for corporations and those already in power since they produce the myth that one person cannot make a difference, or that 2-3 people can't make a difference, but the LINUX people I talked about back in November show that this is patently false.

I'm not Bob Barr and I think that sometimes larger government and powerful centralized governmental organizations are the answer. I would love to hear how Libertarians think the airline industry would work without the FAA or how well Southern Blacks would be educated without the Dept. of Education. But organizations remove the individual and her sense of importance from the equation, and when that happens moral choices don't carry the weight they once did (since no one will notice or be directly harmed by our actions). Top-down, organizational approaches are sometimes useful. Sometimes, however, they are a fiction useful for corporations and those already in power since they produce the myth that one person cannot make a difference, or that 2-3 people can't make a difference, but the LINUX people I talked about back in November show that this is patently false.

1 comment:

Speaking of victory gardens and equipment, I'm gonna need my shovel back soon.

-Nick

Post a Comment