I've been trying to say what Bill Maher said--which is OK because he gets paid to say these things, and I just write this blog.

I've been trying to say what Bill Maher said--which is OK because he gets paid to say these things, and I just write this blog.

28 February 2009

Yeah, What Maher Said...

I've been trying to say what Bill Maher said--which is OK because he gets paid to say these things, and I just write this blog.

I've been trying to say what Bill Maher said--which is OK because he gets paid to say these things, and I just write this blog.

Labels:

consumerism,

democracy,

incoherent rant,

laziness

26 February 2009

Americans are Kinda Wussy

President Obama (who is, again, the Anti-Christ or Hitler or whoever) delivered a pretty impressive speech the other night, but I'm not sure how this presidency is going to turn out. Obama is treating us like we're grown ups capable of taking action that is in our best long-term interest; this could be his fatal mistake. Behold, Greg Burns of the Chicago Tribune:

Of course, Obama does difficult things, like sartorially kicking a union leader in the balls:

Feeling confident yet? Didn't think so.This is just ridiculous. Why are we relying on Obama for our spine? Is that why conservatives love/d Bush? Because he made the morally dubious decisions that they didn't feel complicit in--all the while shielding them from any real sense of sacrifice. Obama can give us hope, and he can call on us to do the difficult things, and we'll like it. As long as it's rhetoric. When we have to do some difficult things for ourselves, well, then we don't feel confident. And that, of course, is our President's fault, not our own.

Despite mostly upbeat reviews about President Barack Obama's pep talk to the nation, reality intervened Wednesday.

Investors went back to selling stocks as more bad news about the nation's shaky finances overshadowed the administration's efforts to lift the gloom.

Speeches, it turns out, only go so far in restoring confidence.

"In essence, the market has said, 'So what?' " noted Gary Gehm, a principal at Legg Mason Investment Counsel in Chicago. Economists generally put a lot of stock in confidence, the belief that things will get better, not worse. That's what makes investors invest and consumers spend....

So despite the president's hopeful message, the Dow Jones industrial average fell 80 points, closing near the lows of 1997, with no sign of a comeback....

At the moment, though, it's tough to get money moving. As Legg Mason's Gehm encourages wealthy individuals to entrust their assets to his professional managers, he said, he's hearing a lot of the same concerns: "I'm scared. I don't know what to do."

"It makes it so much more difficult to get people to commit to a program."

Of course, Obama does difficult things, like sartorially kicking a union leader in the balls:

Labels:

awesomeness,

consumerism,

democracy,

incoherent rant,

laziness,

politics

22 February 2009

Gitmo and Medieval Beatings

Gitmo prisoner, victim of beatings from 'middle ages,' finally transferred to BritainI think that Carolyn Dinshaw should be consulted about this immediately.

On Monday, Binyam Mohamed will become the first Guantanamo Bay detainee to be released since President Obama took office....Mohamed will leave the infamous prison in Cuba a bruised and battered man, a victim of "dozens" of beatings – what "should have been left behind in the middle ages," according to his British lawyer....

Mohamed, 30, was found to be suffering from a litany of physical problems: bruising, organ damage, stomach complaints, malnutrition, sores to his feet and hands, and severe damage to ligaments, according to the British newspaper. And then there are his emotional and psychological problems, worsened by Guantánamo guards' refusal to provide counseling.

21 February 2009

Islamic Medieval Poetry...Because You Wish You Were This Awesome

"On A Little Man With A Very Large Beard," by Isaac Ben Khalif

"On A Little Man With A Very Large Beard," by Isaac Ben KhalifHow can thy chin that burden bear?

Is it all gravity to shock?

Is it to make the people stare?

And be thyself a laughing stock? When I behold thy little

feet

After thy beard obsequious run,I always fancy that I meet

Some father followed by his son. A man like thee

scarce e'er appeared--

A beard like thine--where shall we find it?

Surely thou cherishest thy beard

In hopes to hide thyself behind it.

19 February 2009

It's Always the Last Place you Look, or A Revised Orals Prospectus

[Author's Note: This is the last version of my Orals prospectus. If this one doesn't go through, I think I'm quitting. Really. It is a version of what came before, but if you compare the two, there are very few superficial similarities...which I a good thing, I hope.]

[Author's Note: This is the last version of my Orals prospectus. If this one doesn't go through, I think I'm quitting. Really. It is a version of what came before, but if you compare the two, there are very few superficial similarities...which I a good thing, I hope.]Monsters and the Construction of Community in Medieval Literature

A little more than seventy years ago, the venerable J.R.R. Tolkien urged Anglo-Saxonists to rethink their approach to Beowulf. Up to this point it had often been considered a poor example of Old English poetry, but Tolkien thought in order to understand the poem as a poem one must examine its monsters. They were not, as the prevailing wisdom ran, “an inexplicable blunder of taste”; instead, he argued they were “essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem.”[1] Thus began the genealogy of monster theory in medieval literature.

Over the years the approaches have changed: in 1936 Tolkien thought a study of Beowulf’s monsters would lead to the recognition of its literary merits and its placement within a specific genre. Contemporary medieval monster theorists, however, are more attracted to the analysis of monsters as boundary figures. The general shift in approach may have moved from formalism and structuralism to post-structuralism and cultural criticism, but the focus has never strayed from the monsters themselves.

Whether those monsters are medieval creations like the Grendelkin and Chretien de Troyes’ Harpin or their more contemporary brethren like Dracula and Freddy Kreuger, they may be characterized by a single tenet: monsters are what they are because they are both physically and culturally transgressive.[2] This formulation transcends both cultural and historical contexts, but how monsters break these rules, on the other hand, is wholly dependent on the specifics of culture and history. Beowulf’s Grendel and Bram Stoker’s Dracula are not the same in their goals or methods, but their transgressions still fall into either the physical or cultural category. Grendel has glowing eyes and steel-like claws; Dracula is undead and can turn into a bat. Grendel is inimical to the weapons and armor so important to the humans of the poem and mocks the feast hall by making men into the meal; Dracula drains the Life Force from his victims and unleashes female sexuality in a way that threatens the Victorian sensibilities of the male

characters.

Each transgression (be it Grendel’s cannibalism or Dracula’s shape-shifting) necessarily marks a boundary—for without a line there is no crossing, no transgression. For Jeffrey Jerome Cohen and the other medieval monster theorists who largely follow his lead, the boundary is limned by the creator(s) of the monster. It is through their monsters that they tell us what they believe should not be possible, what they believe one should not think, speak, or do.[3] In short, monsters have always done the job from which they got their names: they point out and show the line between “us” and “them,” this side and the Other side.[4] Such a function was as true for the Victorian era as it was for our era of examination, the Middle Ages. It has also led Cohen to describe monsters as “the primary vehicle for the representation of Otherness in the Middle

Ages,” a statement on which there is widespread consensus.[5]

This consensus deals with a functional analysis of monsters. Gone are the days of trying to identify Grendel or Harpin ontologically; the question of what they actually were is of less interest than the question of what they do in texts and the effects of those actions on an extratextual scale. As boundary figures, monsters symbolize the Other as they define knowledge and community values by demarcating their outer limits.[6] Such a reading of monsters is not new and relies heavily on the Lacanian theory of the mirror stage—in which the infant uses her image in the glass to create an imago, or false vision of her Self. Key for monster theorists is the exteriority of the image: the use of a mirror’s image creates the Self, but at the same instant introduces the structural possibility of the Other.[7] Lacan’s ideas have been extended by Hayden White into the realm of cultural criticism; he theorizes that communities must use “ostensive self definition by negation” to think of themselves as communities.[8] For White, examples of medieval wildmen served to define what authors meant by “civilized,” “us,” or even “human.” The distinction is one that easily extends from wildmen to monsters, where they are agents of the Other and the negative by which a definition is created. Such a reading has gained traction with monster theorists. Most have accepted the premise that because communities are unable to craft positivist definitions of themselves, they use monsters as didactic exempla of transgressive behavior to work out what is not a part of their community and, conversely, help outline what is a part of it.

Such is the current state of monster theory as it applies to the Middle Ages: we mostly agree that monsters negatively define the cultures and communities that created them. However, no one has undertaken a serious, sustained interrogation of the specific processes by which monsters help form communities. I am interested in moving past what monsters do (boundary markers) to examine how monsters function and the consequences of those processes; that interest has brought me to the two following questions:

- What is the process by which communities adopt, adapt, or create monsters?

- How do monsters work to strengthen the communities’ sense of themselves?

The examination will begin by exploring the process by which the monsters of these two texts were (re)created. In Beowulf, I will look at how the Grendelkin threaten the community through their relationship to weapons. Certainly this culturally transgressive behavior is one among many they exhibit (cannibalism, silence, dress, etc.). But in a world where weapons have names and even lineages, it is significant that both Grendel and his mother do not use weapons favored by the human warriors of the poem and that Grendel himself seems to be enchanted against harm from Geatish and Danish swords. Likewise, a close study of Yvain shows the giant, Harpin, to be a threat to chivalric sexual mores because he is attempting to extort a lord’s beautiful, virginal daughter. Since he is usually shorthand for libidinal excess, a giant carrying off of a virgin is an obvious threat to female purity, but Harpin’s actions are much more subtle and significant: he does not desire her but instead plans on prostituting the courtly maiden to his knaves and dishwashers—the lowest members of his household. In Harpin, Chretien was able to present a threat not only to the idealized female purity upon which courtly love was built but also to the heteronormative vision of masculinity upon which chivalry was built.[9]

Through the above examination, I hope to establish that communities (re)create monsters based on their own highly-prized cultural practices—in this case weapon use and sexual customs. The monster is created from foundational cultural beliefs and so can be thought of as a constellation of transgressions. These transgressions cut to the quick, threatening or questioning cultural practices that are, arguably, the defining characteristics of any community. To help explain how monsters define and strengthen a community’s sense of itself, I will turn to Benedict Anderson’s theory of imagined communities.[10] In both texts the monster is defeated, a sort of tableau vivant that plays out again and again—whether it be in classical, medieval, Victorian, or contemporary horror fiction. Grendel’s defeat by Beowulf and Harpin’s by Yvain signify not only the triumph of the individual heroes, but also the triumph of the cultural mores they defend. These mores, according to Anderson, are the very things that bind individuals together, making—and remaking—socially-constructed communities that are based on specific shared traits. It is in a community’s identity-formation that the function of the monster is most important; as a constellation of transgressive qualities, the monster is defeated, reaffirming a particular value set and in turn (re)defining or (re)constructing the community. If we can understand the construction of medieval communities, we can better comprehend how they envisioned themselves and their place in the world. Such an understanding has consequences far beyond the monsters in Beowulf or Yvain, for through their nightmares these communities tell us who they were.

Notes:

1 “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics.” Proceedings of the British Academy 22 (1936): 245-95. 261.

2 Jeffrey Jerome Cohen. “Monster Culture (Seven Theses).” Monster Theory: Reading Culture. Ed. Jeffrey Jerome Cohen. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1996. 3-25. 6.

3 For limits on thought, see Cohen’s “The Limits of Knowing: Monsters and the Regulation of Medieval Poplar Culture.” Medieval Folklore 3 (1994): 1-37. For limits on speech, see David Williams’ Deformed Discourse: The Function of the Monster in Mediaeval Thought and Literature. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s UP, 1996. For limits on action, see John Block Friedman’s The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought. Syracuse: Syracuse UP, 2000.

4 The Latin monstro means to “show” or “point out” and is the root of the Modern English “demonstrate.”

5 “The Use of Monsters and the Middle Ages.” SELIM: Journal of the Spanish Society for Medieval English Language and Literature 2 (1992): 47-69. 49 (Emphasis mine).

On this consensus, see also: Noël Carroll. The Philosophy of Horror. New York: Routledge, 1990; Albrecht Classen. “Medieval Answers to the Strange World Outside: Foreigners and the Foreign as Cultural Challenges and Catalysts.” Demons: Mediators Between This World and the Other. Eds. Ruth Petzoldt and Paul Neubauer. Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1998. 133-51; Edward J. Ingebretsen. “Monster-Making: A Politics of Persuasion.” Journal of American Culture 21.2 (1998): 25-34; and Franco Moretti. “Dialectic of Fear.” Signs Taken for Wonders: Essays in the Sociology of Literary Forms. Trans. Susan Fischer, David Forgacs, and David Miller. London:

Verso, 1988. 83-108.

6 About a monster’s physical (taxonomic) transgressions there is much to say. However, it is here that I must focus on the cultural side of the ledger. For more on physical transgressions and boundaries of knowledge, see Cohen’s “The Limits of Knowing: Monsters and the Regulation of Medieval Poplar Culture.”

7 Lacan associates this self/Other split that occurs during the mirror stage with Freud’s Innenwelt and Umwelt. See Lacan’s “The Mirror Stage” in Ecrits: A Selection. Trans. Alan Sheridan. New York: Norton, 1977. 1-10.

8 Tropics of Discourse: Essays in Cultural Criticism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1978. 151-52.

9 See: Lee Ramsey. Chivalric Romances: Popular Literature in Medieval England. Bloomington: U of Indiana P, 1983, and Cohen. “Decapitation and Coming of Age: Constructing Masculinity and the Monstrous.” Arthurian Yearbook III. Ed. Keith Busby. New York: Garland, 1993. 171-90.

10 Anderson discusses imagined communities in the context of modern nationalism and its rise, but mutatis mutandis, his theory will be applicable to community formation, whether or not nationalism is involved.

Labels:

Arthuriana,

Beowulf,

Grendelkin,

incoherent rant,

medieval,

monsters,

OE,

poetry,

theory

18 February 2009

27% Reading Completion

This is another meme from Facebook, and I'm boycotting all further Facebook-notes-as-updated-chain-emails. However, I figure this blog is enough about solipsism that I can get away with posting it here (and it's easier to avoid, too).

I replaced numbers 36 and 98 because The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe is a part of Lewis' Chronicles of Narnia and Hamlet is obviously a part of Shakespeare's complete works.

Apparently the BBC reckons most people will have only read 6 of the 100 books here. I've also changed the instructions.

2) The Lord of the Rings, J.R.R. Tolkien

3) Jane Eyre, Charlotte Bronte

4) Harry Potter series, JK Rowling (just read the first one)*

5) To Kill a Mockingbird, Harper Lee

6) The Bible (all of it...except the Apocrypha)

7) Wuthering Heights, Emily Bronte

8) Nineteen Eighty-Four, George Orwell

9) His Dark Materials, Philip Pullman

10) Great Expectations, Charles Dickens*

11) Little Women, Louisa M. Alcott

12) Tess of the D'Urbervilles, Thomas Hardy

13) Catch 22, Joseph Heller

14) Complete Works of Shakespeare (haven't read the histories...and I ain't gonna)

15) Rebecca, Daphne Du Maurier

16) The Hobbit, J.R.R. Tolkien

17) Birdsong, Sebastian Faulk

18) Catcher in the Rye, JD Salinger

19) The Time Traveller's Wife, Audrey Niffenegger

20) Middlemarch, George Eliot

21) Gone With The Wind, Margaret Mitchell

22) The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald

23) Bleak House, Charles Dickens

24) War and Peace, Leo Tolstoy*

25) The Hitch Hiker's Guide to the Galaxy, Douglas Adams*

26) Brideshead Revisited, Evelyn Waugh*

27) Crime and Punishment, Fyodor Dostoyevsky*

28) Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck

29) Alice in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll

30) The Wind in the Willows, Kenneth Grahame

31) Anna Karenina, Leo Tolstoy*

32) David Copperfield, Charles Dickens

33) Chronicles of Narnia, C.S. Lewis

34) Emma, Jane Austen

35) Persuasion, Jane Austen

36) Beloved, Toni Morrison

37) The Kite Runner, Khaled Hosseini*

38) Captain Corelli's Mandolin, Louis De Bernieres

39) Memoirs of a Geisha, Arthur Golden

40) Winnie the Pooh, A.A. Milne*

41) Animal Farm, George Orwell

42) The Da Vinci Code, Dan Brown

43) One Hundred Years of Solitude, Gabriel Garcia Marquez*

44) A Prayer for Owen Meaney, John Irving

45) The Woman in White, Wilkie Collins*

46) Anne of Green Gables, L.M. Montgomery

47) Far From The Madding Crowd, Thomas Hardy

48) The Handmaid's Tale, Margaret Atwood*

49) Lord of the Flies, William Golding

50) Atonement, Ian McEwan*

51) Life of Pi, Yann Martel*

52) Dune, Frank Herbert*

53) Cold Comfort Farm, Stella Gibbons

54) Sense and Sensibility, Jane Austen

55) A Suitable Boy, Vikram Seth

56) The Shadow of the Wind, Carlos Ruiz Zafon

57) A Tale Of Two Cities, Charles Dickens

58) Brave New World, Aldous Huxley

59) The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time, Mark Haddon

60) Love In The Time Of Cholera, Gabriel Garcia Marquez*

61) Of Mice and Men, John Steinbeck

62) Lolita, Vladimir Nabokov*

63) The Secret History, Donna Tartt

64) The Lovely Bones, Alice Sebold

65) Count of Monte Cristo, Alexandre Dumas

66) On The Road, Jack Kerouac

67) Jude the Obscure, Thomas Hardy

68) Bridget Jones's Diary, Helen Fielding

69) Midnight's Children, Salman Rushdie

70) Moby Dick, Herman Melville*

71) Oliver Twist, Charles Dickens

72) Dracula, Bram Stoker

73) The Secret Garden, Frances Hodgson Burnett

74) Notes From A Small Island, Bill Bryson

75) Ulysses, James Joyce*

76) The Bell Jar, Sylvia Plath*

77) Swallows and Amazons, Arthur Ransome

78) Germinal, Emile Zola

79) Vanity Fair, William Makepeace Thackeray

80) Possession, A.S. Byatt

81) A Christmas Carol, Charles Dickens

82) Cloud Atlas, David Mitchell

83) The Color Purple, Alice Walker*

84) The Remains of the Day, Kazuo Ishiguro

85) Madame Bovary, Gustave Flaubert

86) A Fine Balance, Rohinton Mistry

87) Charlotte's Web, E.B. White

88) The Five People You Meet In Heaven, Mitch Albom

89) Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

90) The Faraway Tree Collection, Enid Blyton

91) Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad

92) The Little Prince, Antoine De Saint-Exupery

93) The Wasp Factory, Iain Banks

94) Watership Down, Richard Adams

95) A Confederacy of Dunces, John Kennedy Toole

96) A Town Like Alice, Nevil Shute

97) The Three Musketeers, Alexandre Dumas

98) Gravity's Rainbow, Thomas Pynchon*

99) Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Roald Dahl*

100) Les Miserables, Victor Hugo (never finished it)*

Read: 27

Love: 14

*Want to read: 24

I replaced numbers 36 and 98 because The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe is a part of Lewis' Chronicles of Narnia and Hamlet is obviously a part of Shakespeare's complete works.

Apparently the BBC reckons most people will have only read 6 of the 100 books here. I've also changed the instructions.

- All books I have read are in bold

- All books in red font I love.

- All books with an asterisk I plan on reading.

- Tally of read/loved books are at the bottom.

2) The Lord of the Rings, J.R.R. Tolkien

3) Jane Eyre, Charlotte Bronte

4) Harry Potter series, JK Rowling (just read the first one)*

5) To Kill a Mockingbird, Harper Lee

6) The Bible (all of it...except the Apocrypha)

7) Wuthering Heights, Emily Bronte

8) Nineteen Eighty-Four, George Orwell

9) His Dark Materials, Philip Pullman

10) Great Expectations, Charles Dickens*

11) Little Women, Louisa M. Alcott

12) Tess of the D'Urbervilles, Thomas Hardy

13) Catch 22, Joseph Heller

14) Complete Works of Shakespeare (haven't read the histories...and I ain't gonna)

15) Rebecca, Daphne Du Maurier

16) The Hobbit, J.R.R. Tolkien

17) Birdsong, Sebastian Faulk

18) Catcher in the Rye, JD Salinger

19) The Time Traveller's Wife, Audrey Niffenegger

20) Middlemarch, George Eliot

21) Gone With The Wind, Margaret Mitchell

22) The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald

23) Bleak House, Charles Dickens

24) War and Peace, Leo Tolstoy*

25) The Hitch Hiker's Guide to the Galaxy, Douglas Adams*

26) Brideshead Revisited, Evelyn Waugh*

27) Crime and Punishment, Fyodor Dostoyevsky*

28) Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck

29) Alice in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll

30) The Wind in the Willows, Kenneth Grahame

31) Anna Karenina, Leo Tolstoy*

32) David Copperfield, Charles Dickens

33) Chronicles of Narnia, C.S. Lewis

34) Emma, Jane Austen

35) Persuasion, Jane Austen

36) Beloved, Toni Morrison

37) The Kite Runner, Khaled Hosseini*

38) Captain Corelli's Mandolin, Louis De Bernieres

39) Memoirs of a Geisha, Arthur Golden

40) Winnie the Pooh, A.A. Milne*

41) Animal Farm, George Orwell

42) The Da Vinci Code, Dan Brown

43) One Hundred Years of Solitude, Gabriel Garcia Marquez*

44) A Prayer for Owen Meaney, John Irving

45) The Woman in White, Wilkie Collins*

46) Anne of Green Gables, L.M. Montgomery

47) Far From The Madding Crowd, Thomas Hardy

48) The Handmaid's Tale, Margaret Atwood*

49) Lord of the Flies, William Golding

50) Atonement, Ian McEwan*

51) Life of Pi, Yann Martel*

52) Dune, Frank Herbert*

53) Cold Comfort Farm, Stella Gibbons

54) Sense and Sensibility, Jane Austen

55) A Suitable Boy, Vikram Seth

56) The Shadow of the Wind, Carlos Ruiz Zafon

57) A Tale Of Two Cities, Charles Dickens

58) Brave New World, Aldous Huxley

59) The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time, Mark Haddon

60) Love In The Time Of Cholera, Gabriel Garcia Marquez*

61) Of Mice and Men, John Steinbeck

62) Lolita, Vladimir Nabokov*

63) The Secret History, Donna Tartt

64) The Lovely Bones, Alice Sebold

65) Count of Monte Cristo, Alexandre Dumas

66) On The Road, Jack Kerouac

67) Jude the Obscure, Thomas Hardy

68) Bridget Jones's Diary, Helen Fielding

69) Midnight's Children, Salman Rushdie

70) Moby Dick, Herman Melville*

71) Oliver Twist, Charles Dickens

72) Dracula, Bram Stoker

73) The Secret Garden, Frances Hodgson Burnett

74) Notes From A Small Island, Bill Bryson

75) Ulysses, James Joyce*

76) The Bell Jar, Sylvia Plath*

77) Swallows and Amazons, Arthur Ransome

78) Germinal, Emile Zola

79) Vanity Fair, William Makepeace Thackeray

80) Possession, A.S. Byatt

81) A Christmas Carol, Charles Dickens

82) Cloud Atlas, David Mitchell

83) The Color Purple, Alice Walker*

84) The Remains of the Day, Kazuo Ishiguro

85) Madame Bovary, Gustave Flaubert

86) A Fine Balance, Rohinton Mistry

87) Charlotte's Web, E.B. White

88) The Five People You Meet In Heaven, Mitch Albom

89) Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

90) The Faraway Tree Collection, Enid Blyton

91) Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad

92) The Little Prince, Antoine De Saint-Exupery

93) The Wasp Factory, Iain Banks

94) Watership Down, Richard Adams

95) A Confederacy of Dunces, John Kennedy Toole

96) A Town Like Alice, Nevil Shute

97) The Three Musketeers, Alexandre Dumas

98) Gravity's Rainbow, Thomas Pynchon*

99) Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Roald Dahl*

100) Les Miserables, Victor Hugo (never finished it)*

Read: 27

Love: 14

*Want to read: 24

14 February 2009

OMG, Tainted Peanut Butter? Blame the FDA (Again)

But for the love of Mr Peanut, let's not blame ourselves. People have been worried about tainted peanut butter, tomatoes, spinach, etc. for years now, and the latest news from West Texas isn't helping any. From The Raw Story:

But for the love of Mr Peanut, let's not blame ourselves. People have been worried about tainted peanut butter, tomatoes, spinach, etc. for years now, and the latest news from West Texas isn't helping any. From The Raw Story:The shrieks over the latest food-bourne illness outbreak has made me start thinking. What was it that we said before? From the NYT on 12 December 2006:The discovery of dead rodents and bird feathers in a Plainview, Texas plant of the Peanut Corporation of America, already implicated in a deadly salmonella outbreak, prompted a recall of all its products, officials said....

The company's facility in Blakely, Georgia has been blamed for a widespread food poisoning outbreak knowingly shipped contaminated peanut butter and had mold growing on its ceilings and walls.

The salmonella outbreak took place between September 1 and January 9, with 501 people infected in 43 states and one more person reported ill in Canada, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), which is collaborating with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on the investigation....

An FDA inspection report released Wednesday found 12 instances between June 2007 and September 2008 where the firm's own testing revealed that its products were contaminated by salmonella and the PCA nonetheless shipped the product.

"Two outbreaks of bacterial poisoning from fresh produce over the past three months, and a possible third that is still under investigation, raise doubts about the Food and Drug Administration’s ability to inspect and monitor conditions on the nation’s farms and in the plants that package and process their produce....So, the NYT wants us to load more regulatory duties onto the backs of agencies that have proven they can't keep us safe. I wonder why they can't? Those with a Liberal bent will tell you it's because they are underfunded. Those with a Conservative bent will tell you it's because they're government agencies and breed laziness. Either way, it's not the agencies' fault. It's ours.

Meanwhile, the agency’s workload has been rising steadily as health-conscious Americans eat more fruit and vegetables....At a minimum, Congress needs to provide the F.D.A. with more money and more inspectors to monitor the safety of fresh produce all the way from field to consumer. It should also abandon the fiction that voluntary guidelines to ensure safe food production can do the job, and insist instead on some kind of mandatory regulation. It is also time to revive the long-languishing notion that all of the government’s disparate food regulation activities should be combined into a single, fully empowered agency."

We've bought into the agri-business model hook, line, and sinker. We got hooked, reeled in, and now we're sunk. When/if we think of farmers, we usually think of Old McDonald's farm.

But it's more like Old McDonald Farms LLC, a subsidiary of ConAgra Foods.

But it's more like Old McDonald Farms LLC, a subsidiary of ConAgra Foods. When you rely on something as big as the Peanut Corporation of America, you are asking for trouble because you're relying on a large corporation to act ethically. A corporation may be legally considered a person, but it cannot be morally or ethically considered a person. Sooner or later, the corporation acts dishonestly in service of the bottom line or its shareholders. Wendell Berry, in his Unsettling of America, gives the striking example of the Sierra Club investing in Exxon in the 70s (17). To expect otherwise is to expect the snake not to bite the turtle.

When you rely on something as big as the Peanut Corporation of America, you are asking for trouble because you're relying on a large corporation to act ethically. A corporation may be legally considered a person, but it cannot be morally or ethically considered a person. Sooner or later, the corporation acts dishonestly in service of the bottom line or its shareholders. Wendell Berry, in his Unsettling of America, gives the striking example of the Sierra Club investing in Exxon in the 70s (17). To expect otherwise is to expect the snake not to bite the turtle.So, like Berry, I say that we should be more "responsible consumers," which would necessitate us becoming critical consumers (we would "refuse to purchase the less good"), moderate consumers (we would know our "needs and would not purchase what [we] did not need"), and--at least partial--producers (24). Berry contends:

The household that prepares its own meals in its own kitchen with some intelligent regard for nutritional value, and thus depends on the grocer only for selected raw materials, exercises an influence on the food industry that reaches from the store all the way back to the seedsman. The household that produces some or all of its own food will have a proportionately greater influence....[The producer/consumer] can choose, and exert the influence of his choosing, because he has given himself choices. He is not confined to the negativity of his complaint. (24-25)Now what the NYT--and everyone who's carping about tainted food and evil corporations--are advocating is the confinement of the consumer by "the negativity of his complaint"; in some ways the expectations we've placed on the FDA, the USDA, and corporations who provide our food have injected a sense of learned helplessness in the average American. We don't take responsibility for our food choices because we have ceded our responsibility--and, therefore, our power--to organizations. These organizations are theoretically beholden to us, but they are so big, they have no inherent self: they remove the individuals who comprise them from the stated purpose of the organization and from personal responsibility. Thus, the CEO who ships jobs overseas because it is better for the shareholders, though it is worse for the country in which he lives. Thus, the geologist who explores for the oil that eventually pollutes the air his child will breathe. Thus the FDA agent who is pressured to do more inspections and does them more quickly or sloppily which eventually leads to peanut factories that have rat feces and feathers above the processing area.

This would not, of course, happen if we returned to a regional or local model of food production.

Michael Pollan has written about the results of agri-business, and Carlo Petrini has made it his mission in life to evangalize the slow food movement. We don't have to choose one of the other, however. Certainly, we could create NeoVictory Gardens, a modern version of something our grandparents did during World War II. This is a radical change, but it's also a change that some people are lamenting Bush didn't urge us to make--that is, war sacrifices. (Again, I ask where's the personal responsibility? Why does someone have to force us to effect change in our lives?)

Michael Pollan has written about the results of agri-business, and Carlo Petrini has made it his mission in life to evangalize the slow food movement. We don't have to choose one of the other, however. Certainly, we could create NeoVictory Gardens, a modern version of something our grandparents did during World War II. This is a radical change, but it's also a change that some people are lamenting Bush didn't urge us to make--that is, war sacrifices. (Again, I ask where's the personal responsibility? Why does someone have to force us to effect change in our lives?)Of course, a NeoVictory Garden is a difficult change to make beause some people don't have yards, and a window box can only produce herbs in most cases. So why not shop at farmer's markets? Why not purchase locally-made or locally-sourced foods? It's more expensive, but you're paying for inefficiency. And that is a good thing, I think.

Ineffeciency in the food industry means more jobs because of redundancy--more small farms and processing plants scattered throughout the nation means more managers, more farmers, more machinery, more people to produce that machinery, etc.

It also requires more responsibility for the consumer. More smaller companies also means less effective centralized oversight, so the FDA can't save the day (and also can't be the punching bag when people get sick). Let's imagine a company called The Willamette Valley Peanut Corp. that services only the Willamette Valley area. It would be more responsibile to and less removed from it consumers. Compare the Peanut Corporation of America, which supplied millions of peanuts to dozens of different companies making everything from Publix's crap-tastic Spicy Trail Mix to Clif Bars, which are supposed to be "all natural" and "70% organic." But people had never heard of the PCA before, and it took a lot of work to figure out how far its tainted products had spread throughout America. Willamette Valley Peanut Corp., on the other hand, would supply to just regional companies, would be more visible to its end consumers, and would suffer from competition if it produced an inferior peanut. These things aren't (or weren't) real concerns for PCA--especially the last one since the company was too big for smaller, localized companies to compete with. Even if the fictional WVP grew to dominate the area, it's not as hard to start up and compete with a regional power as it is to compete with the Wal*Mart of peanut production.

The end result of all of this worry and hand-wringing is likely to be more regulation, larger government, and higher taxes. I am not so die-hard libertarian that I cannot see the value in these things. Sometimes. But this is not one of those times. If we were able to reward inefficiency and regionalization in our food production, we would be able to more easily re-assume and exercise our duties as consumer-producers, responsible consumers, and individuals. I should acknowledge that this little tirade, as Berry admitted in his book, is implicitly (and now explicitly) directed against liberalism as it is practised today.

It has become, to some extent at least, an argument against institutional solutions. Such solutions necessarily fail to solve the problems to which they are addressed because, by definition, they cannot consider the real causes. The only real, practical, hope-givingway to remedy the fragmentation that is the diseaseof the modern spirit is a small and humble way--a way that a government or agency or organization or institution will never think of, though a person may think of it: one must begin in one's own life the private solutions that can only in turn become public solutions. (23)

I'm not Bob Barr and I think that sometimes larger government and powerful centralized governmental organizations are the answer. I would love to hear how Libertarians think the airline industry would work without the FAA or how well Southern Blacks would be educated without the Dept. of Education. But organizations remove the individual and her sense of importance from the equation, and when that happens moral choices don't carry the weight they once did (since no one will notice or be directly harmed by our actions). Top-down, organizational approaches are sometimes useful. Sometimes, however, they are a fiction useful for corporations and those already in power since they produce the myth that one person cannot make a difference, or that 2-3 people can't make a difference, but the LINUX people I talked about back in November show that this is patently false.

I'm not Bob Barr and I think that sometimes larger government and powerful centralized governmental organizations are the answer. I would love to hear how Libertarians think the airline industry would work without the FAA or how well Southern Blacks would be educated without the Dept. of Education. But organizations remove the individual and her sense of importance from the equation, and when that happens moral choices don't carry the weight they once did (since no one will notice or be directly harmed by our actions). Top-down, organizational approaches are sometimes useful. Sometimes, however, they are a fiction useful for corporations and those already in power since they produce the myth that one person cannot make a difference, or that 2-3 people can't make a difference, but the LINUX people I talked about back in November show that this is patently false.

Labels:

consumerism,

democracy,

fear,

food,

incoherent rant,

laziness,

politics

12 February 2009

51 Songs

This is a revision of a meme that's been going around Facebook; I did the 25 version there, but not with all my songs loaded onto Media Player. This is the result.

1) "Alphabet Street," Prince from The Very Best of Prince

2) "Before my Time," Johhny Cash from American III: Solitary Man

2) "Before my Time," Johhny Cash from American III: Solitary Man

3) "One & A Rainbow," Ugly American from Boom Boom Baby

4) "Free of Hope," Indigo Girls from Sweet Relief II: The Gravity of the Situation

5) "Serve the Servants," Nirvana from In Utero

6) "Karma Police," Radiohead from OK Computer

7) "Star People 97," George Michael from Ladies and Gentlemen: The Best of George Michael Disc 2

8) "The Needle Has Landed," Neko Case from Fox Confessor Brings the Flood

9) "Sowing on the Mountain," Woody Guthrie from Muleskinner Blues: The Asch Recordings Vol. 2

10) "Revelation (Mother Earth)," Ozzy Osbourne from Blizzard of Ozz

11) "Tarantula," The Scabs from Freebird

11) "Tarantula," The Scabs from Freebird

12) "She Ain't Goin' Nowhere," Guy Clark from Old No.1 / Texas Cookin'

13) "She Runs Away," Duncan Sheik from Duncan Sheik

14) "Rehab," Amy Winehouse from Back to Black

15) "My Funny Valentine," Chet Baker from My Funny Valentine

16) "Be Yourself," Audioslave from Out of Exile

17) "ABC," Jackson 5 from ABC

18) "I Don't Know Enough About You," Diana Krall from Love Scenes

19) "8:02 PM," For Squirrels from Example

20) "Southern Belles in London Sing," The Faint from Wet From Birth

21) "Across the Wire," Calexico from Feast of Wire

21) "Across the Wire," Calexico from Feast of Wire

22) "Charleston," Django Reinhardt from Djanglologie/USA

23) "Let's Get out of This Country," Camera Obscura from Let's Get out of This Country

24) "Tiny Dancer," Elton John from the soundtrack to Almost Famous

25) "Symphony No. 15 in G Major, K.124:2 Adante," Mozart from Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: The Symphonies Disc 4

26) "Purpose," 311 from 311

27) "Wolves," Garth Brooks from No Fences

28) "Everything Zen," Bush from Sixteen Stone

29) "Songbird," Fleetwood Mac from Rumours

30) "Teardrop," Massive Attack from Mezzanine

31) "Break on Through (To the Other Side)," The Doors from The Doors

31) "Break on Through (To the Other Side)," The Doors from The Doors

32) "Home," 12 Stones from 12 Stones

33) "Woman King," Iron & Wine from Woman King

34) "When I Hit San Antone," Owen Temple from General Store

35) "Diamonds from Sierra Leone," Kanye West from Late Regisration

36) "Let Me Drown," Soundgarden from Superunknown

37) "In Your Mind," Built to Spill from Ancient Melodies of the Future

38) "Oh Yeah," Mos Def and Talib Kweli from Black Star

39) "Vasoline," Stone Temple Pilots from Purple

40) "Gettin' By," Jerry Jeff Walker from Viva Terlingua!

41) "Everything is Broken [Alternate Version]," Bob Dylan from The Bootleg Series, Vol. 8: Tell Tale Signs

41) "Everything is Broken [Alternate Version]," Bob Dylan from The Bootleg Series, Vol. 8: Tell Tale Signs

42) "Oh!," Sleater-Kinney from One Beat

43) "Lullaby in Rhythm, Pt. 1," Charlie Parker from The Legendary Dial Masters, Vol. 2

44) "Melody of Love," Frank Sinatra from The Capitol Collector's Series

45) "Recycled Air," The Postal Service from Give Up

46) "Just Wait," Blues Traveller from Four

47) "Kind of Girl," Low from Things we Lost in the Fire

48) "If You Want Blood (You've Got It)," AC/DC from Highway to Hell

49) "Love & Communication," Cat Power from The Greatest

50) "Leaning Against the Wall," Kings of Convenience from Quiet is the New Loud

51) "It's Not Supposed to Be That Way," Willie Nelson from Phases and Stages

1) "Alphabet Street," Prince from The Very Best of Prince

2) "Before my Time," Johhny Cash from American III: Solitary Man

2) "Before my Time," Johhny Cash from American III: Solitary Man3) "One & A Rainbow," Ugly American from Boom Boom Baby

4) "Free of Hope," Indigo Girls from Sweet Relief II: The Gravity of the Situation

5) "Serve the Servants," Nirvana from In Utero

6) "Karma Police," Radiohead from OK Computer

7) "Star People 97," George Michael from Ladies and Gentlemen: The Best of George Michael Disc 2

8) "The Needle Has Landed," Neko Case from Fox Confessor Brings the Flood

9) "Sowing on the Mountain," Woody Guthrie from Muleskinner Blues: The Asch Recordings Vol. 2

10) "Revelation (Mother Earth)," Ozzy Osbourne from Blizzard of Ozz

11) "Tarantula," The Scabs from Freebird

11) "Tarantula," The Scabs from Freebird12) "She Ain't Goin' Nowhere," Guy Clark from Old No.1 / Texas Cookin'

13) "She Runs Away," Duncan Sheik from Duncan Sheik

14) "Rehab," Amy Winehouse from Back to Black

15) "My Funny Valentine," Chet Baker from My Funny Valentine

16) "Be Yourself," Audioslave from Out of Exile

17) "ABC," Jackson 5 from ABC

18) "I Don't Know Enough About You," Diana Krall from Love Scenes

19) "8:02 PM," For Squirrels from Example

20) "Southern Belles in London Sing," The Faint from Wet From Birth

21) "Across the Wire," Calexico from Feast of Wire

21) "Across the Wire," Calexico from Feast of Wire22) "Charleston," Django Reinhardt from Djanglologie/USA

23) "Let's Get out of This Country," Camera Obscura from Let's Get out of This Country

24) "Tiny Dancer," Elton John from the soundtrack to Almost Famous

25) "Symphony No. 15 in G Major, K.124:2 Adante," Mozart from Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: The Symphonies Disc 4

26) "Purpose," 311 from 311

27) "Wolves," Garth Brooks from No Fences

28) "Everything Zen," Bush from Sixteen Stone

29) "Songbird," Fleetwood Mac from Rumours

30) "Teardrop," Massive Attack from Mezzanine

31) "Break on Through (To the Other Side)," The Doors from The Doors

31) "Break on Through (To the Other Side)," The Doors from The Doors32) "Home," 12 Stones from 12 Stones

33) "Woman King," Iron & Wine from Woman King

34) "When I Hit San Antone," Owen Temple from General Store

35) "Diamonds from Sierra Leone," Kanye West from Late Regisration

36) "Let Me Drown," Soundgarden from Superunknown

37) "In Your Mind," Built to Spill from Ancient Melodies of the Future

38) "Oh Yeah," Mos Def and Talib Kweli from Black Star

39) "Vasoline," Stone Temple Pilots from Purple

40) "Gettin' By," Jerry Jeff Walker from Viva Terlingua!

41) "Everything is Broken [Alternate Version]," Bob Dylan from The Bootleg Series, Vol. 8: Tell Tale Signs

41) "Everything is Broken [Alternate Version]," Bob Dylan from The Bootleg Series, Vol. 8: Tell Tale Signs42) "Oh!," Sleater-Kinney from One Beat

43) "Lullaby in Rhythm, Pt. 1," Charlie Parker from The Legendary Dial Masters, Vol. 2

44) "Melody of Love," Frank Sinatra from The Capitol Collector's Series

45) "Recycled Air," The Postal Service from Give Up

46) "Just Wait," Blues Traveller from Four

47) "Kind of Girl," Low from Things we Lost in the Fire

48) "If You Want Blood (You've Got It)," AC/DC from Highway to Hell

49) "Love & Communication," Cat Power from The Greatest

50) "Leaning Against the Wall," Kings of Convenience from Quiet is the New Loud

51) "It's Not Supposed to Be That Way," Willie Nelson from Phases and Stages

10 February 2009

Orals Proposal: A Before and After Snapshot

This is only the first part of the proposal, and it is unfinished, but it's coming along fairly nicely. It's not as bad in any case.

Before:

Before:

For years—at least since John Block Friedman’s 1981 book The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought and Jeffrey J. Cohen’s debut on the scene in the early 1990s—monster theory has been overwhelmingly concerned with reading monsters as marginal figures that demarcate the cultures that create them. Freddy Krueger, Frankenstein’s monster, the Giant of Mount St Michel, the Grendelkin, or Polyphemus mark the boundaries of what is and is not possible. Perhaps more importantly, they serve as outer boundaries of what an individual can or cannot think, speak, or do. [1] In short, they have usually been read as “the primary vehicle for the representation of Otherness in the Middle Ages”; [2] in fact, on this there is a rare and surprisingly widespread consensus.

This widespread consensus, however, has made for an awkward moment in monster theory. Such agreement has left many unsure as to how we should proceed, and some have focused their attentions on other projects. Indeed, conversations with fellow members of the BABEL Working Group such as Cohen, Eileen Joy, and Karl Steel have shown that while monsters are still a source of discussion, scholarly interest in them is beginning to wane in favor of attendant issues (hybridity, sexuality, medieval concepts of the human, etc.). As many who were once heavily involved in monster theory have foreseen, academic agreement quickly becomes academic stagnation. Thus, what was once the study of characters who could petrify with fear is itself in danger of sinking into the swamp and becoming petrified by consensus.

What have not been agreed upon—or even hotly debated—are the functions of monsters as boundary figures. We may agree that as symbols of the Other they demarcate, and we may even agree (though to a lesser extent) on how they go about doing so. But to my knowledge no serious, sustained interrogation has been performed on their function as means of community-formation. Boundary figures by their very nature create an inside and outside. As the Lacanian imago immediately introduces the structural possibility of self/not self, so too does the monster introduce the structural possibility of us/them. [3] This interpretation denies any positivist model for definition, and it is the basis on which Hayden White forms his idea of “ostensive self-definition by negation.” [4] He argues that cultures are largely unable to create an overall definition of what they are and so point to a thing that they are not. Following White’s theory of how the concept of “wildness” served to define “human” or “civilized,” we may read monsters as boundary figures that aid in the creation of a culture’s (negative) definition—of defining what it is by demarcating what it is not. [5]

[1] For limits on thought, see Jeffrey J. Cohen’s “The Limits of Knowing: Monsters and the Regulation of Medieval Poplar Culture.” Medieval Folklore 3 (1994): 1-37. For limits on speech, see David Williams’ Deformed Discourse: The Function of the Monster in Mediaeval Thought and Literature. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s UP, 1996. For limits on action, see John Block Friedman’s The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought. Syracuse: Syracuse UP, 2000.

[2] The Use of Monsters and the Middle Ages.” SELIM: Journal of the Spanish Society for Medieval English Language and Literature 2 (1992): 47-69. p. 49 (Emphasis mine).

On this consensus, see also: Noël Carroll, The Philosophy of Horror (New York: Routledge, 1990); Albrecht Classen, “Medieval Answers to the Strange World Outside: Foreigners and the Foreign as Cultural Challenges and Catalysts,” in Demons: Mediators Between This World and the Other, eds. Ruth Petzoldt and Paul Neubauer (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1998); Edward J. Ingebretsen, “Monster-Making: A Politics of Persuasion.” Journal of American Culture 21.2 (1998): 25-34; and Franco Moretti, “Dialectic of Fear,” in Signs Taken for Wonders: Essays in the Sociology of Literary Forms, trans. Susan Fischer, David Forgacs, and David Miller. (London: Verso, 1988).

[3] Lacan associates this self/Other split that occurs during the mirror stage with Freud’s Innenwelt and Umwelt. See Lacan’s “The Mirror Stage” in Ecrits: A Selection. Trans. Alan Sheridan. New York: Norton, 1977.

[4] Tropics of Discourse: Essays in Cultural Criticism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1978. pp. 151-52.

[5] US Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart produced a lasting example of ostensive negative definition in 1964. Admitting that he could not define pornography, he then stated “I know it when I see it, and the motion picture involved in this case is not that” (Jacobellis v. Ohio. 378 U.S. 184. Supreme Ct. of the US. 22 June 1964).

After:

Back in 1936, the venerable J.R.R. Tolkien urged Anglo-Saxonists to rethink their approach to Beowulf. Up to this point the poem had been considered a useful historical document and a poor poem, but Tolkien thought that—in order to understand the poem as a poem we ought to examine its monsters. They were not, as so many had previously thought, “an inexplicable blunder of taste”; instead, he argued they were “essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem.” [1] And so began the genealogy of monster theory in medieval literature.

Back in 1936, the venerable J.R.R. Tolkien urged Anglo-Saxonists to rethink their approach to Beowulf. Up to this point the poem had been considered a useful historical document and a poor poem, but Tolkien thought that—in order to understand the poem as a poem we ought to examine its monsters. They were not, as so many had previously thought, “an inexplicable blunder of taste”; instead, he argued they were “essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem.” [1] And so began the genealogy of monster theory in medieval literature.

Over the years the approaches and theories have changed, mostly in step with overall academic trends. In 1936 Tolkien thought study of Beowulf’s monsters would lead to an understanding of its literary merits and its generic placement. Currently, medieval monster theorists are more concerned with analyzing monsters as marginal, boundary figures. The general (but not total) shift in approach may have moved from a formalist and structuralist bent to post-structuralism and cultural criticism, but the focus of the approach has never wavered. Monsters.

Monsters—be they medieval creations like the Grendelkin or Chretien de Troyes’ Harpin, or their more contemporary brethren like Dracula or Freddy Kreuger—may be characterized by a single tenet: monsters are what they are (ontologically, functionally, culturally) because they do not play by physical or cultural rules. [2] That notion is acultural, ahistorical, but what is wholly dependent on specifics of culture and history is how monsters break these rules. Beowulf’s Grendel and Bram Stoker’s Dracula are not the same in their goals or their methods, but their transgressions still adhere to the dual categories. Grendel has glowing eyes, is as large as thirty men and has steel-like claws; Dracula is (un)dead and can turn into a bat. Grendel will not or cannot speak, is inimical to the weapons and armor so important to the humans of the poem, and creates a perverse mockery of the feast hall by making men the meal; Dracula drains the Life Force from his victims and unleashes female sexuality in a way that threatens the Victorian sensibilities of Seward, Holmwood, and Van Helsing.

Each transgression (whether it be Grendel feasting on human flesh or Dracula turning into a bat) necessarily marks a boundary, for without a line there is no crossing, no transgression. For Jeffrey Jerome Cohen—and the other medieval monster theorists who largely follow his lead—the boundary is imagined by the creator(s) of the monster. It is through their nightmares that these people and their cultures tell us about themselves. It is through their monsters that they tell us what they believe should not be possible, what they believe one should not think, speak, or do. [3] In short, monsters really do the job to which they are etymologically linked: they point out and show the line between “us” and “them,” this side and the Other side. [4] Such a function was as true for the Victorian era as it was for our era of examination, the Middle Ages. It has lead Cohen to pronounce monsters “the primary vehicle for the representation of Otherness in the Middle Ages,” a statement on which there is widespread consensus. [5]

This consensus deals with a functional analysis of monsters. Gone are the days of trying to identify Grendel or Harpin ontologically; what they actually were is of less interest than analysis of what they do in texts and the effects of those actions on a broader, extratextual scale. We may agree that as boundary figures, monsters symbolize the Other they demarcate, conjuring the specter of its existence event as they attempt to dissuade serious consideration of it. Such a reading of monsters is nothing new and relies heavily on the Lacanian theory of the imago introducing the structural possibility of the Other as a integral part of identity formation. [6] The notion that monsters work to construct what cultural critic Hayden White calls “ostensive self definition by negation” has gained traction over the years, and most monster theorists have accepted—to varying degrees—the premise that communities, largely unable to craft a positivist model, point to examples of what they are not in order to create a definition of what they are. [7] For White, examples of medieval wildmen served to define what authors meant by “civilized,” “us,” or even “human.” This theory is easily extended to monsters to explain their function in the creation of a specific community’s (negative) definition by providing didactic exempla of what is not a part of that community.

[1] “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics.” Proceedings of the British Academy 22 (1936): 245-95. p. 261.

[2] Jeffrey Jerome Cohen. “Monster Culture (Seven Theses).” Monster Theory: Reading Culture. Ed. Jeffrey Jerome Cohen. (Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1996), 6.

[3] For limits on thought, see Jeffrey J. Cohen’s “The Limits of Knowing: Monsters and the Regulation of Medieval Poplar Culture.” Medieval Folklore 3 (1994): 1-37. For limits on speech, see David Williams’ Deformed Discourse: The Function of the Monster in Mediaeval Thought and Literature. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s UP, 1996. For limits on action, see John Block Friedman’s The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought. Syracuse: Syracuse UP, 2000.

[4] The Latin monstro means to “show” or “point out” and is the root of the Modern English “demonstrate.”

[5] The Use of Monsters and the Middle Ages.” SELIM: Journal of the Spanish Society for Medieval English Language and Literature 2 (1992): 47-69. p. 49 (Emphasis mine).

On this consensus, see also: Noël Carroll, The Philosophy of Horror (New York: Routledge, 1990); Albrecht Classen, “Medieval Answers to the Strange World Outside: Foreigners and the Foreign as Cultural Challenges and Catalysts,” in Demons: Mediators Between This World and the Other, eds. Ruth Petzoldt and Paul Neubauer (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1998); Edward J. Ingebretsen, “Monster-Making: A Politics of Persuasion.” Journal of American Culture 21.2 (1998): 25-34; and Franco Moretti, “Dialectic of Fear,” in Signs Taken for Wonders: Essays in the Sociology of Literary Forms, trans. Susan Fischer, David Forgacs, and David Miller. (London: Verso, 1988).

[6] Lacan associates this self/Other split that occurs during the mirror stage with Freud’s Innenwelt and Umwelt. See Lacan’s “The Mirror Stage” in Ecrits: A Selection. Trans. Alan Sheridan. New York: Norton, 1977.

[7] Tropics of Discourse: Essays in Cultural Criticism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1978. pp. 151-52.

US Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart produced a lasting example of ostensive negative definition in 1964. Admitting that he could not define pornography, he then stated “I know it when I see it, and the motion picture involved in this case is not that” (Jacobellis v. Ohio. 378 U.S. 184. Supreme Ct. of the US. 22 June 1964).

Before:

Before:For years—at least since John Block Friedman’s 1981 book The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought and Jeffrey J. Cohen’s debut on the scene in the early 1990s—monster theory has been overwhelmingly concerned with reading monsters as marginal figures that demarcate the cultures that create them. Freddy Krueger, Frankenstein’s monster, the Giant of Mount St Michel, the Grendelkin, or Polyphemus mark the boundaries of what is and is not possible. Perhaps more importantly, they serve as outer boundaries of what an individual can or cannot think, speak, or do. [1] In short, they have usually been read as “the primary vehicle for the representation of Otherness in the Middle Ages”; [2] in fact, on this there is a rare and surprisingly widespread consensus.

This widespread consensus, however, has made for an awkward moment in monster theory. Such agreement has left many unsure as to how we should proceed, and some have focused their attentions on other projects. Indeed, conversations with fellow members of the BABEL Working Group such as Cohen, Eileen Joy, and Karl Steel have shown that while monsters are still a source of discussion, scholarly interest in them is beginning to wane in favor of attendant issues (hybridity, sexuality, medieval concepts of the human, etc.). As many who were once heavily involved in monster theory have foreseen, academic agreement quickly becomes academic stagnation. Thus, what was once the study of characters who could petrify with fear is itself in danger of sinking into the swamp and becoming petrified by consensus.

What have not been agreed upon—or even hotly debated—are the functions of monsters as boundary figures. We may agree that as symbols of the Other they demarcate, and we may even agree (though to a lesser extent) on how they go about doing so. But to my knowledge no serious, sustained interrogation has been performed on their function as means of community-formation. Boundary figures by their very nature create an inside and outside. As the Lacanian imago immediately introduces the structural possibility of self/not self, so too does the monster introduce the structural possibility of us/them. [3] This interpretation denies any positivist model for definition, and it is the basis on which Hayden White forms his idea of “ostensive self-definition by negation.” [4] He argues that cultures are largely unable to create an overall definition of what they are and so point to a thing that they are not. Following White’s theory of how the concept of “wildness” served to define “human” or “civilized,” we may read monsters as boundary figures that aid in the creation of a culture’s (negative) definition—of defining what it is by demarcating what it is not. [5]

[1] For limits on thought, see Jeffrey J. Cohen’s “The Limits of Knowing: Monsters and the Regulation of Medieval Poplar Culture.” Medieval Folklore 3 (1994): 1-37. For limits on speech, see David Williams’ Deformed Discourse: The Function of the Monster in Mediaeval Thought and Literature. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s UP, 1996. For limits on action, see John Block Friedman’s The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought. Syracuse: Syracuse UP, 2000.

[2] The Use of Monsters and the Middle Ages.” SELIM: Journal of the Spanish Society for Medieval English Language and Literature 2 (1992): 47-69. p. 49 (Emphasis mine).

On this consensus, see also: Noël Carroll, The Philosophy of Horror (New York: Routledge, 1990); Albrecht Classen, “Medieval Answers to the Strange World Outside: Foreigners and the Foreign as Cultural Challenges and Catalysts,” in Demons: Mediators Between This World and the Other, eds. Ruth Petzoldt and Paul Neubauer (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1998); Edward J. Ingebretsen, “Monster-Making: A Politics of Persuasion.” Journal of American Culture 21.2 (1998): 25-34; and Franco Moretti, “Dialectic of Fear,” in Signs Taken for Wonders: Essays in the Sociology of Literary Forms, trans. Susan Fischer, David Forgacs, and David Miller. (London: Verso, 1988).

[3] Lacan associates this self/Other split that occurs during the mirror stage with Freud’s Innenwelt and Umwelt. See Lacan’s “The Mirror Stage” in Ecrits: A Selection. Trans. Alan Sheridan. New York: Norton, 1977.

[4] Tropics of Discourse: Essays in Cultural Criticism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1978. pp. 151-52.

[5] US Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart produced a lasting example of ostensive negative definition in 1964. Admitting that he could not define pornography, he then stated “I know it when I see it, and the motion picture involved in this case is not that” (Jacobellis v. Ohio. 378 U.S. 184. Supreme Ct. of the US. 22 June 1964).

After:

Back in 1936, the venerable J.R.R. Tolkien urged Anglo-Saxonists to rethink their approach to Beowulf. Up to this point the poem had been considered a useful historical document and a poor poem, but Tolkien thought that—in order to understand the poem as a poem we ought to examine its monsters. They were not, as so many had previously thought, “an inexplicable blunder of taste”; instead, he argued they were “essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem.” [1] And so began the genealogy of monster theory in medieval literature.

Back in 1936, the venerable J.R.R. Tolkien urged Anglo-Saxonists to rethink their approach to Beowulf. Up to this point the poem had been considered a useful historical document and a poor poem, but Tolkien thought that—in order to understand the poem as a poem we ought to examine its monsters. They were not, as so many had previously thought, “an inexplicable blunder of taste”; instead, he argued they were “essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem.” [1] And so began the genealogy of monster theory in medieval literature.Over the years the approaches and theories have changed, mostly in step with overall academic trends. In 1936 Tolkien thought study of Beowulf’s monsters would lead to an understanding of its literary merits and its generic placement. Currently, medieval monster theorists are more concerned with analyzing monsters as marginal, boundary figures. The general (but not total) shift in approach may have moved from a formalist and structuralist bent to post-structuralism and cultural criticism, but the focus of the approach has never wavered. Monsters.

Monsters—be they medieval creations like the Grendelkin or Chretien de Troyes’ Harpin, or their more contemporary brethren like Dracula or Freddy Kreuger—may be characterized by a single tenet: monsters are what they are (ontologically, functionally, culturally) because they do not play by physical or cultural rules. [2] That notion is acultural, ahistorical, but what is wholly dependent on specifics of culture and history is how monsters break these rules. Beowulf’s Grendel and Bram Stoker’s Dracula are not the same in their goals or their methods, but their transgressions still adhere to the dual categories. Grendel has glowing eyes, is as large as thirty men and has steel-like claws; Dracula is (un)dead and can turn into a bat. Grendel will not or cannot speak, is inimical to the weapons and armor so important to the humans of the poem, and creates a perverse mockery of the feast hall by making men the meal; Dracula drains the Life Force from his victims and unleashes female sexuality in a way that threatens the Victorian sensibilities of Seward, Holmwood, and Van Helsing.

Each transgression (whether it be Grendel feasting on human flesh or Dracula turning into a bat) necessarily marks a boundary, for without a line there is no crossing, no transgression. For Jeffrey Jerome Cohen—and the other medieval monster theorists who largely follow his lead—the boundary is imagined by the creator(s) of the monster. It is through their nightmares that these people and their cultures tell us about themselves. It is through their monsters that they tell us what they believe should not be possible, what they believe one should not think, speak, or do. [3] In short, monsters really do the job to which they are etymologically linked: they point out and show the line between “us” and “them,” this side and the Other side. [4] Such a function was as true for the Victorian era as it was for our era of examination, the Middle Ages. It has lead Cohen to pronounce monsters “the primary vehicle for the representation of Otherness in the Middle Ages,” a statement on which there is widespread consensus. [5]

This consensus deals with a functional analysis of monsters. Gone are the days of trying to identify Grendel or Harpin ontologically; what they actually were is of less interest than analysis of what they do in texts and the effects of those actions on a broader, extratextual scale. We may agree that as boundary figures, monsters symbolize the Other they demarcate, conjuring the specter of its existence event as they attempt to dissuade serious consideration of it. Such a reading of monsters is nothing new and relies heavily on the Lacanian theory of the imago introducing the structural possibility of the Other as a integral part of identity formation. [6] The notion that monsters work to construct what cultural critic Hayden White calls “ostensive self definition by negation” has gained traction over the years, and most monster theorists have accepted—to varying degrees—the premise that communities, largely unable to craft a positivist model, point to examples of what they are not in order to create a definition of what they are. [7] For White, examples of medieval wildmen served to define what authors meant by “civilized,” “us,” or even “human.” This theory is easily extended to monsters to explain their function in the creation of a specific community’s (negative) definition by providing didactic exempla of what is not a part of that community.

[1] “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics.” Proceedings of the British Academy 22 (1936): 245-95. p. 261.

[2] Jeffrey Jerome Cohen. “Monster Culture (Seven Theses).” Monster Theory: Reading Culture. Ed. Jeffrey Jerome Cohen. (Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1996), 6.

[3] For limits on thought, see Jeffrey J. Cohen’s “The Limits of Knowing: Monsters and the Regulation of Medieval Poplar Culture.” Medieval Folklore 3 (1994): 1-37. For limits on speech, see David Williams’ Deformed Discourse: The Function of the Monster in Mediaeval Thought and Literature. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s UP, 1996. For limits on action, see John Block Friedman’s The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought. Syracuse: Syracuse UP, 2000.

[4] The Latin monstro means to “show” or “point out” and is the root of the Modern English “demonstrate.”

[5] The Use of Monsters and the Middle Ages.” SELIM: Journal of the Spanish Society for Medieval English Language and Literature 2 (1992): 47-69. p. 49 (Emphasis mine).

On this consensus, see also: Noël Carroll, The Philosophy of Horror (New York: Routledge, 1990); Albrecht Classen, “Medieval Answers to the Strange World Outside: Foreigners and the Foreign as Cultural Challenges and Catalysts,” in Demons: Mediators Between This World and the Other, eds. Ruth Petzoldt and Paul Neubauer (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 1998); Edward J. Ingebretsen, “Monster-Making: A Politics of Persuasion.” Journal of American Culture 21.2 (1998): 25-34; and Franco Moretti, “Dialectic of Fear,” in Signs Taken for Wonders: Essays in the Sociology of Literary Forms, trans. Susan Fischer, David Forgacs, and David Miller. (London: Verso, 1988).

[6] Lacan associates this self/Other split that occurs during the mirror stage with Freud’s Innenwelt and Umwelt. See Lacan’s “The Mirror Stage” in Ecrits: A Selection. Trans. Alan Sheridan. New York: Norton, 1977.

[7] Tropics of Discourse: Essays in Cultural Criticism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1978. pp. 151-52.

US Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart produced a lasting example of ostensive negative definition in 1964. Admitting that he could not define pornography, he then stated “I know it when I see it, and the motion picture involved in this case is not that” (Jacobellis v. Ohio. 378 U.S. 184. Supreme Ct. of the US. 22 June 1964).

08 February 2009

07 February 2009

Reaching up to Touch the Floor

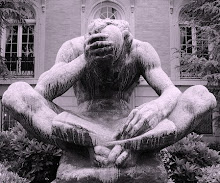

So, yeah. That's sort of how I feel at this point, like I've been going about this thing the wrong way. I've tightened up to the point that it's difficult for me to think creatively about my proposal. I've no trouble thinking critically; thanks to a lot of great support from my friends, I think I have a good idea of the areas that were problematic (and on some of these, there was new and different widespread concensus!). What I'm having trouble with is remedying the problem areas. I know what's wrong, but I'm so overwhelmed by the project and its argument that I can't hold any 2 portions of it in my head for more than a few seconds...and forget trying to re-examine the relationship between 2 or more portions of the proposal. That is far beyond the scope of someone who just today forgot one of the key primary sources for this research project (remembered Harpin but forgot Chretien when talking to Eric Lutrell today). So I'm going to work only on this paragraph tonight--and probably for just a few minutes. I imagine a lot of it is about to go by the wayside...

Original:

This widespread consensus, however, has made for an awkward moment in monster theory. Such agreement has left many unsure as to how we should proceed, and some have focused their attentions on other projects. Indeed, conversations with fellow members of the BABEL Working Group such as Cohen, Eileen Joy, and Karl Steel have shown that while monsters are still a source of discussion, scholarly interest in them is beginning to wane in favor of attendant issues (hybridity, sexuality, medieval concepts of the human, etc.). As many who were once heavily involved in monster theory have foreseen, academic agreement quickly becomes academic stagnation. Thus, what was once the study of characters who could petrify with fear is itself in danger of sinking into the swamp and becoming petrified by consensus.Well, even I have to admit that this paragraph is pretty bad. Let's see what I can do here.

Revised:

Academic consensus is a rare bird, and one of the reasons for this is the stagnation that often follows in its wake. Broad-scale agreement kills discussion and ceases movement: we relinquish our places at the vanguard where we advanced new and risky ideas to bivouac in familiar territory where we produce prescriptive statements. Our sense of inquiry leaves us.I started fading there at the end. But it provokes lots of questions in my head: How do monsters function as boundary figures? Is it by dint of their physical description/appearance? Their actions? Their rupture of "normal" narrative events? Their troubling and overshadowing of other, more formal aspects of the works that contain them? Their peculiar cultural markers (such as cannibalism, silence/gibberish, clothing)?

One might argue that the momentum of monster theory has begun to wain, our forward progress has slowed. Perhaps each scholar associated with monster theory has begun to keep one eye open for more attractive, vibrant areas of inquiry. Perhaps when there is nothing left to argue, there is nothing left to say. Perhaps--though we be blind men touching different parts of the proverbial elephant--we have decided that is it, indeed, an elephant. We are far from done, for we have not even begun to understand how the elephant works. We may agree on the definition and even function of monsters in medieval texts, but that is just the "what"; we have only begun to ask the "how" and the "why" of that function.

Do these aspects themselves reinforce the boundary via fear? If so, how is fear employed? Is it fear of the monster and of the Other (psychoanalytic) or fear of ending up like the monster who always suffers the same fate in what amounts to a morality tale (structuralist)? Is it fear of what is necessarily on the other side of that boundary? Is what is on the other side of the monster what is actually deeply-seated in all of us (Lacanian extimacy)?

I think the waters are sufficiently muddied...but I'm no closer to a cogent prospectus. Great.

06 February 2009

1200 is for pussies, we do the 8th century

This, according to my own calculations, is the single greatest utterance by an Anglo-Saxonist in the history of ever. I am forever in Eileen's debt, for this has brightened my day, given me direction in my life, and reinvigorated my academic drive.

Monsters are the Washington Generals of Literature

I guess my committee chair was right: there are some ginormous structuralist underpinnings in this project. I was re-reading Cohen's introduction to Monster Theory (for the eleventy billionth time), and I realized that I am assuming a general plot for monsters within texts. It may not be the main plot: it could be an incidental story or the overarching theme of the work, but it almost always turns out the same. The general story arc for monsters is that they threaten and then lose. It's so simple that many people have relied on it without stating it explicity or, having stated it explicitly, did not place it within its proper theoretical context.

I guess my committee chair was right: there are some ginormous structuralist underpinnings in this project. I was re-reading Cohen's introduction to Monster Theory (for the eleventy billionth time), and I realized that I am assuming a general plot for monsters within texts. It may not be the main plot: it could be an incidental story or the overarching theme of the work, but it almost always turns out the same. The general story arc for monsters is that they threaten and then lose. It's so simple that many people have relied on it without stating it explicity or, having stated it explicitly, did not place it within its proper theoretical context.But it is a structuralist precept in the classic sense. Grimm, Propp, et al. often got bogged down in detailing minute variations of story types--trying to create some sort of Linnean taxonomy of every single type and variant of that type. It not only was so ambitious as to be impossible, but it seemed to be of limited use even in its ideal form. On the other side of the register, Jung, Campbell, et al. often generalized similarities to the point that they were so vague and all-encompassing that one saw them in everything. How does one make a story without a protagonist and antagonist? How does the protagonist then not become a variant of (or response to) The Hero?

But as Edward Ingebretsen once wrote (I paraphrase): the monster exists to be killed, we must be the one who kills it, and it can never be our fault. Whether that monster is a personification of a cultural anxiety (Frankenstein's monster, Dracula, Freddy, witches) or a partial reification of an actual personage (the Japanese in WWII propaganda posters, OJ Simpson, Native Americans), the story plays out the same way. The monster threatens. We, the people, resist and fight (sometimes via proxy in the hero, sometimes not). The monster dies by our hand. Our anxieties are termporarily assuaged.

It's not a very interesting plot line, but it's just a terrifically general skeleton plot--a thing that Tolkien once complained was, no matter the text, either "wild, or trivial, or typical." The thing about it is its ability to