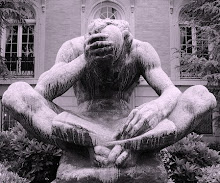

My Orals proposal was rejected!

My Orals proposal was rejected!Soooooo, since it bounced like a Bernie Madoff check, I guess I have my work cut out for me. I need to figure out what the hell's confusing about this thing; the trouble is, like my students, I'm so close to it that I can't see the confusing parts, the logically flawed parts. It seems to make total sense to me, but not to a group of non-medievalists who don't know what the hell monster theory is.

I was already pretty concerned about oversimplifying monster theory as a movement, so it's ironic that it was decided I didn't explain it clearly/simply enough. Maybe I should contextualize monster theory within the post-structuralist and cultural criticism movement, but I footnoted the proposal pretty heavily. I didn't think I had to explain much in the way of who two of the biggest names in medieval monster theory are; I mean, I think I introduced my sources pretty well (not the USSC Justice, but that was an parenthetical, explanatory note, not a supporting/resource note).

I also heard that they were confused a bit by the primary texts--that because they weren't medievalists, they didn't quite follow what I planned to do with/to Harpin and Grendel. I'm not at all sure what to do about this problem; I was unaware that I was writing to a general academic audience. I thought I was writing to my chair since he and other medieval-types will be on the Orals Committee, but now I have to do the most difficult thing a writer can attempt (besides adapting Ulysses to the screen). I have to think like a non-medievalist, and I honestly don't know if I can do that. I've put a call out to medievalists and non-medievalists for some help in identifying the problems,

but I can't wait. I have to start out now, so I'm going to take it bird by bird, as Anne Lamott would say.

but I can't wait. I have to start out now, so I'm going to take it bird by bird, as Anne Lamott would say.First off, the initial paragraph.

Original:

For years—at least since John Block Friedman’s 1981 book The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought and Jeffrey J. Cohen’s debut on the scene in the early 1990s—monster theory has been overwhelmingly concerned with reading monsters as marginal figures that demarcate the cultures that create them. Freddy Krueger, Frankenstein’s monster, the Giant of Mount St Michel, the Grendelkin, or Polyphemus mark the boundaries of what is and is not possible. Perhaps more importantly, they serve as outer boundaries of what an individual can or cannot think, speak, or do. In short, they have usually been read as “the primary vehicle for the representation of Otherness in the Middle Ages”; in fact, on this there is a rare and surprisingly widespread consensus.

Redux:

Redux:Back in 1936, the venerable J.R.R. Tolkien urged Anglo-Saxonists to rethink their approach to Beowulf. Up to this point, the poem had largely been used as a historical document rather than a poetic work, but Tolkien thought we should not ignore the monsters of the poem. They were not, as so many had previously thought, "an inexplicable blunder of taste"; instead, he argued they were "essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem" (261). And so began the genealogy of monster theory in medieval literature.

Over the years, the approaches and theories have changed with the shifting sands of academic trends. Tolkien thought a closer examination of the monsters of Beowulf would lead to a better understanding of its literary merits, its generic placement, and the theme of a hero's courage. Currently, medieval monster theorists are concerned less with these aspects of the poem; at least since John Block Friedman’s 1981 book The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought and Jeffrey J. Cohen’s debut on the scene in the early 1990s, monster theory has been largely concerned with reading monsters as marginal figures that demarcate the cultures that create them.

The general shift in approach may have moved from a formalist bent to post-structuralism and cultural criticism, but the focus of the approach never has. Monsters--be they medieval creations like the Grendelkin or the Giant of Mount St Michel or their contemporary brethren like Frankenstein’s monster, Dracula, or Freddy Kreuger--mark boundaries. For Tolkien it was the boundary of what is and is not a poem, a lyric, or a hero. For Cohen and other contemporary monster theorists, it is the boundary of what is and is not possible and of what an individual can or cannot think, speak, or do. In short, contemporary monster theory has usually read monsters as “the primary vehicle for the representation of Otherness in the Middle Ages”; in fact, on this there is a rare and surprisingly widespread consensus.

There, that can't be worse than before...or can it?

2 comments:

I like #2 better, I really like knowing what the arc looks like..and also how surely you describe its changing shape. I really like this, reads like the beginning of the intro to your book!

Better now than later. At least you won't get screwed at your defense, like some people I know.

OK, it was an MA and the situation was completely different--but I'm still bitter. I think that's the only reason I got a PhD--to redeem myself.

I'd love to take a closer look at it. Perhaps as a generalist who teaches Beowulf every year, I can offer an outsider's perspective.

Post a Comment